complex cyst on kidney has grown 5 mm i n 6:months what to do?

- Educational Review

- Open up Access

- Published:

CT and MR imaging of cystic renal lesions

Insights into Imaging volume 11, Article number:5 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Cystic renal lesions are a common incidental finding on routinely imaging examinations. Although a benign simple cyst is usually piece of cake to recognize, the same is not true for complex and multifocal cystic renal lesions, whose differential diagnosis includes both neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions. In this review, we will show a series of cases in order to provide tips to identify benign cysts and differentiate them from malignant ones.

Key points

-

Cystic renal lesions are a common incidental finding on routinely imaging examinations.

-

Benign elementary cyst is usually easy to recognize at imaging.

-

Differential diagnosis of complex and multifocal cystic renal lesions include both neoplastic and non-neoplastic weather condition.

-

The most widely used organisation to allocate cystic renal lesions was introduced past Bosniak in 1984 and revised in 1997.

-

Renal cysts tin can be divided into focal and multifocal.

Introduction

Cystic renal lesions are very commonly encountered at abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Most lesions are asymptomatic and incidentally found, only they can rarely manifest with abdominal hurting, hematuria, and signs of infection (e.one thousand., fever). Although the majority represents simple cysts, their pathologic spectrum is broad and includes developmental, neoplastic, and inflammatory processes.

Ultrasound represents normally the first-line imaging exam of the abdomen and kidney and tin easily recognize simple, fluid-filled renal cysts with the following criteria: homogeneous anechoic content, marked posterior enhancement, and well-divers borders [one, ii].

When these criteria are absent, a cystic renal lesion is classified as a complex cyst [1, 2].

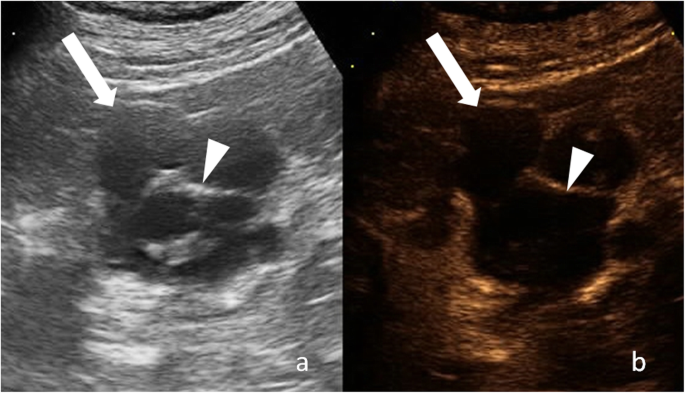

The term "complicated cyst" must be reserved to those cysts, which undergo morphological changes due to documented rupture, hemorrhage, or infection [1, two]. Complex and complicated renal cysts cannot be accurately characterized at ultrasound and usually warrant dissimilarity-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging [ane, 2]. Considering of absenteeism of ionizing radiation and depression-cost contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) is emerging every bit a valuable alternative to contrast-enhanced CT and MR [three, four]. A growing body of prove suggests that CEUS is useful to evaluate the vascularity of both cystic renal and hepatic lesion in real time using microbubble-based, purely intravascular, contrast agents (Fig. i) [3,iv,v,vi,7]. However, the use of CEUS hampered operator dependency and technical limitations due to deep lesion location, bowel interposition, patient body habitus, and patient cooperation [iii, 8]. Knowledge of the imaging characteristics and agreement the pathophysiology of cystic renal lesions helps the radiologist to derive the correct diagnosis.

Cystic renal lesion in a 76-twelvemonth-quondam-human. a Gray-scale ultrasound shows a cystic lesion (arrow) with a thin wall and thin septa (arrowhead), which contains fine calcifications. b Respective CEUS image shows enhancement of cyst wall and septa

A useful strategy for the evaluation of renal cysts is to divide them into focal and multifocal.

In this paper, nosotros will expose radiologists to a series of CT and MRI cases in order to provide tips to identify benign cysts and differentiate them from cancerous ones in adult patients.

CT or MRI: advantages and disadvantages

Contrast-enhanced CT is the modality of choice in evaluating cystic renal masses. Narrow detector thickness (< 1 mm) and intravenous administration of dissimilarity agent are mandatory to detect thin septa and small enhancing nodules [9]. Too, sit-in of enhancing areas helps differentiate solid components from hemorrhage or droppings [10]. MRI is used when CT is contraindicated (e.g., patients with allergy to iodinated contrast amanuensis) or every bit a problem-solving modality for equivocal findings. Indeed, MRI tin can show some septa that are less credible at CT and demonstrate definitive enhancement in those cysts that bear witness only equivocal enhancement at CT [11]. As a outcome, renal cysts can be placed in a higher Bosniak category with MRI than with CT [11].

Focal renal cysts

Focal renal cysts are common in older subjects. Their prevalence, size, and number increase with age, with approximately 30% of people after the fourth decade and 40% after the fifth decade having at least one renal cyst [12, 13]. The bulk is benign elementary renal cysts and can exist diagnosed with conviction. However, cystic renal lesions can have benign besides as malignant causes. Possible malignant causes include renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and metastasis. Since cystic RCCs, beneficial complicated cysts, and other cystic tumors can be radiologically indistinguishable, the goal of imaging when a renal cyst is found is to differentiate a benign "leave-alone" lesion from a lesion that requires treatment.

Bosniak classification system for renal cysts

The nearly widely used system to classify cystic renal lesions was introduced by Bosniak in 1984 and revised in 1997 [14, 15]. This system was originally developed on CT findings, but it can be also used at MRI [11, 16, 17].

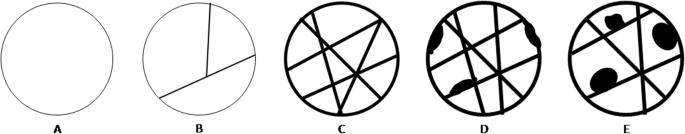

Renal cysts are divided into five categories on the basis of imaging appearance (Table i, Fig. 2). Each Bosniak category reflects the likelihood of cystic RCC that ranges from I (elementary cyst) to IV (cystic tumors). Category I, II, and, IIF cysts are nonsurgical, while categories Three and Iv are surgical.

Imaging features of cystic renal lesions according to Bosniak nomenclature. a Bosniak category I cyst: thin wall. b Bosniak category II cyst: thin wall; few, thin septa. c Bosniak category II-F cyst: minimally thickened wall; several, minimally thickened septa. d Bosniak category III cyst: irregularly thickened wall; several, irregularly thickened septa. e Bosniak category IV cyst: enhancing nodularity; irregularly thickened wall; several, irregularly thickened septa

Imaging findings include attenuation/signal intensity, size, presence of calcifications, septa and enhancing nodularity. Among these, enhancing nodularity is considered the most important predictor of malignancy [18]. At CT, enhancement requires an increase of attenuation of at least 15–twenty HU from unenhanced to the dissimilarity enhanced images [18]. A 10–15 HU alter in attenuation can be due to wrong placement of the region of interest, patient motion, or beam hardening from side by side enhancing renal parenchyma (the and so called "pseudoenhancement") [nineteen]. To overcome this trouble, information technology has been suggested to utilize dual-energy CT, where truthful unenhanced images tin can be replaced by virtual unenhanced images [20]. Iodine quantification and iodine-related attenuation are used to differentiate nonenhancing cysts from enhancing solid masses [20].

In equivocal cases, some other option is to use subtraction MRI to assess the presence or absence of enhancement [21].

Septa are defined as dividing wall within a renal cyst and are best appreciated at MRI than at CT. When present, they tin exist classified as thin, minimally thickened, or grossly thickened and irregular, and every bit enhancing or not-enhancing.

Calcifications are usually easy to recognize at CT simply may exist unapparent at MRI. Despite the importance in predicting the malignancy of solid renal masses, calcifications have limited utility in the Bosniak classification since they tin be establish in the wall or septa of both benign and cancerous cysts [22]. Similarly, the size does non reliably predict the benignity or malignity of a renal cyst. Indeed, larger cysts tin can be benign and small ones tin be cancerous.

Category I renal cysts

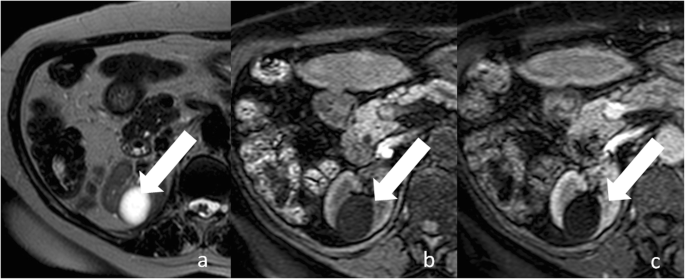

Category I cysts are simple benign cysts. The exact pathogenesis is unknown. It has been suggested that they originate from weakening of the basement membrane of distal convoluted or collecting tubules [23]. Imaging appearance is consistent with h2o content: 0–20 HU attenuation on unenhanced CT, strong hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI sequences, hypointensity on T1-weighted MRI sequences (Figs. 3 and four). The wall is thin, pilus-line, and non-enhancing. Calcifications, septa, and enhancing nodularity are absent. Almost all are benign. In a study including 1700 individuals with at to the lowest degree one renal cyst, only two patients developed a renal neoplasm [12]. Category I renal can grow in size over time. Handling or follow-upwardly are not recommended.

Bosniak category I renal cyst. Centric not-enhanced (a) and dissimilarity-enhanced (b) CT images shows a cyst (arrow) with a sparse and non-enhancing wall

Bosniak category I renal cyst. a Axial T2-weighted MR epitome shows a lesion (arrow) with strong hyperintensity and a thin wall. Respective centric non-enhanced (b) and contrast-enhanced (c) T1-weighted MR images bear witness a hypointense lesion with a sparse and non-enhancing wall

Category II renal cysts

Category Ii renal cysts are slightly more complicated in that they show hair-line wall, and few, thin septa, which can show perceived (not measurable) enhancement (Fig. 5). Fine calcifications or a short segment of slightly thickened calcifications can be present in the wall or septa. Complicated (proteinaceous or hemorrhagic) renal cysts measuring less than 3 cm are also included in the category Two. These cysts show hyperattenuation (> xx HU) on unenhanced CT, high point intensity on unenhanced T1-weighted MRI sequences, and no enhancement, which helps differentiate benign cyst from RCC. Lesion homogeneity and smooth borders also are highly suggestive of a beneficial cyst [24]. In full general, proteinaceous cysts measure 20–40 HU and are anechoic at ultrasound, while hemorrhagic cysts mensurate over 40 l HU and can testify a complex advent at ultrasound [25]. Category II renal cysts are benign, and do not crave treatment or follow-upward.

Bosniak category 2 renal cyst. a Axial non-enhanced CT paradigm shows a lesion with a thin wall (pointer) and a thin septum (arrowhead), which contains fine calcifications. b Corresponding axial contrast-enhanced CT epitome shows enhancement of cyst wall and septum

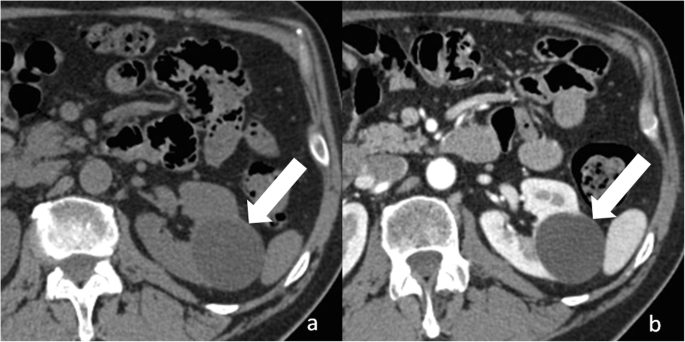

Category IIF renal cysts

Category IIF renal cysts ("F" means follow-upward) are more worrisome than category I and II [15, 26, 27]. The wall and septa can show minimal thickening and perceived (not measurable) enhancement and tin incorporate irregular or nodular calcifications (Fig. 6). Unlike category II cysts, they can incorporate several septa. Complicated renal cysts measuring more than 3 cm are included in the category IIF (Fig. seven). Category IIF renal cysts are beneficial in 75–95% of time [28,29,30]. Imaging follow-upward is required to exclude the malignancy past showing stability over time. However, the optimal interval fourth dimension for follow-up is unclear and is influenced past cyst complexity. Bosniak had suggested that category IIF cysts with minimal complications need a one–ii-year follow-upwardly, while more complex ones require at least a 3–4 yr follow-upwardly [31].

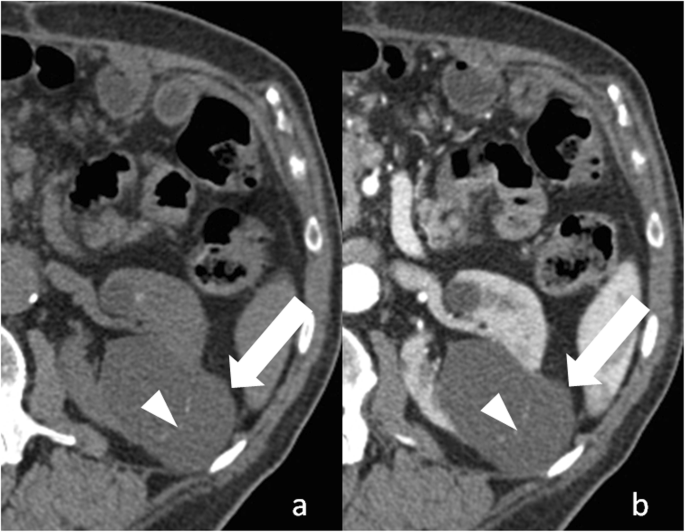

Bosniak category IIF renal cyst. Centric non-enhanced CT paradigm shows a lesion with irregular calcifications within the wall (pointer) and septa (arrowhead)

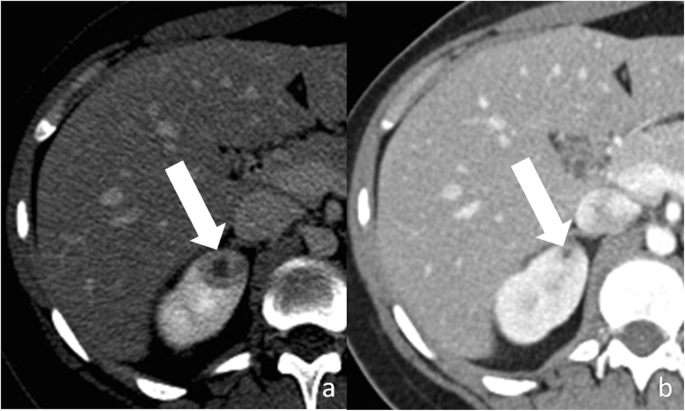

Bosniak category IIF renal cyst. Axial non-enhanced (a) and contrast-enhanced (b) CT images shows a large (> 3 cm) lesion (pointer) with spontaneous hyperattenuation and no enhancement

Category III renal cysts

Category Three renal cysts are indeterminate lesions with a reported malignancy of most 50% [28]. This category includes multilocular cysts, hemorrhagic and infected cysts, multilocular cystic nephroma, and cystic RCC [32]. Wall and septa are irregularly thick, show a measurable enhancement, and can contain thick nodular calcifications (Fig. 8). Septa are increased in number compared to category Ii cysts. Surgical removal of category III renal cysts is recommended because of their increased take chances of malignancy.

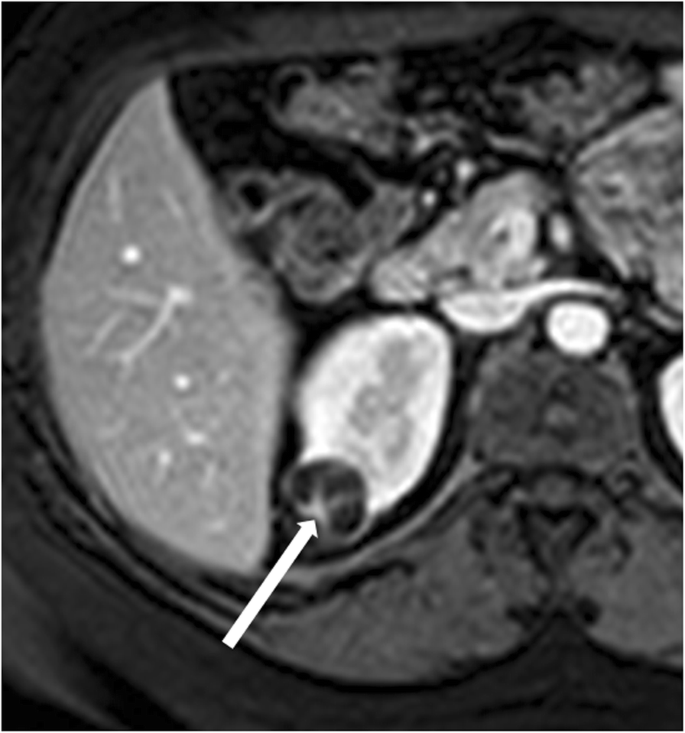

Bosniak category III renal cyst. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows a lesion with thick, enhancing wall and septa (arrow)

Category 4 renal cysts

Category IV renal cysts are considered malignant lesions. Nigh all are RCCs or, more rarely, metastases [32]. Still, in that location are few benign lesions such equally mixed epithelial and stromal tumor (MEST) and cystic angiomyolipomas that tin exist classified as category IV renal cysts [32]. The hallmark of this category is the presence of enhancing nodularity (Fig. 9). These cysts tin likewise contain all findings observed in category III. Surgical removal is strongly recommended.

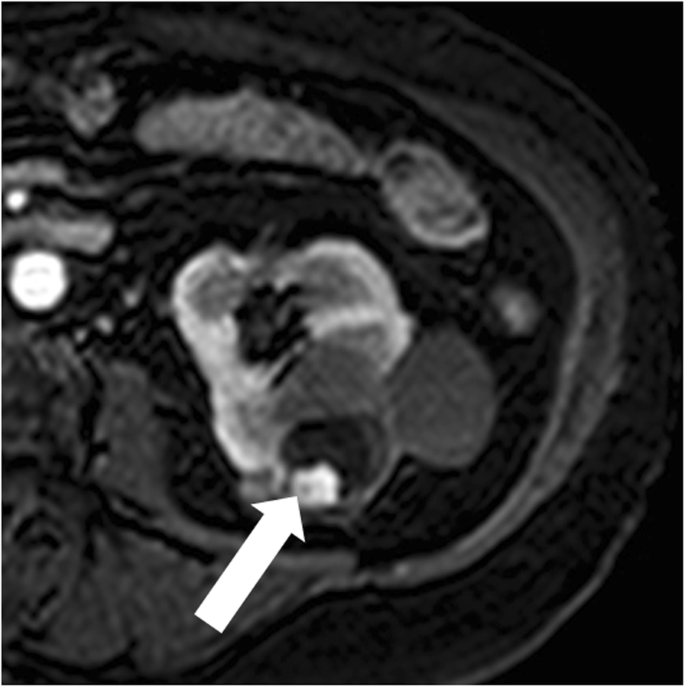

Bosniak category 4 renal cyst. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR paradigm shows a lesion with a peripheral, enhancing, nodule (arrow)

Cystic renal prison cell carcinoma

Cystic RCC is relatively rare and comprises approximately 3–15 % of all cases of RCCs. It is found more commonly in younger age and in females compared with solid RCC [33]. The cystic appearance can be related to their inherent architecture or secondary to cystic degeneration and extensive necrosis [34]. Clear cell type RCC is the most common subtype, followed past papillary and chromophobe RCC. Articulate jail cell blazon RCC can show a dominant cystic component or can ascend in a simple cyst [35]. Multilocular cystic RCC of low malignant potential is a rare variant of articulate cell type RCC with no reported recurrence or metastasis. This tumor is equanimous exclusively by cysts with depression-grade tumor cell [36] and shows a variable imaging appearance, which ranges from category IIF to category Iv renal cysts [35]. Papillary RCC can appear equally a cyst with hemorrhagic or necrotic content and a thick pseudocapsule [35]. Cystic renal RCCs have a more favorable prognosis of all subtypes of RCC: they have a low Fuhrman grade, grow slowly, and rarely metastasize or recur [37].

Renal metastases

Renal metastases are not uncommon, with reported frequencies ranging from vii to 20% at post-mortem studies [38,39,40,41]. The most common primary malignancies are the lung, breast, gastrointestinal tract, and melanoma. CT and MR imaging diagnosis is less frequent because post-mortem studies included microscopic lesions, which are across CT resolution [42, 43].

Renal metastases can bear witness a solid or cystic appearance. The differentiation of renal metastasis from RCC on the ground of CT and MR findings alone may exist impossible [42,43,44]. Notwithstanding, some features are likely to exist distinctive: renal metastases are frequently multiple, bilateral and small [42, 43].

Mixed epithelial and stromal tumors

The MESTs area heterogeneous group of rare renal tumors occurring predominantly in perimenopausal women (female-to-male person ratio, 11:1). The MEST appears equally a well-marginated lesion with a variable proportion of solid and cystic components [45]. Septa and nodules can show heterogeneous and delayed enhancement [45]. MEST tin testify an exophytic growth or herniate into the renal pelvis [45]. Developed cystic nephroma is at present classified inside MEST family due to like histologic and epidemiologic findings [36]. This tumor appears every bit an encapsulated lesion, with cysts of variable size, and thin, variably enhancing, septa [46]. Calcifications are peripheral and curvilinear [46]. Solid components are typically absent-minded [46]. At MRI, the capsule and septa tin can evidence hypointensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images due to the gristly composition. Since imaging features are non-specific, differentiation between MEST and cystic RCC requires pathologic exam.

Renal abscess

Renal abscess is an uncommon entity that usually results from a complication of untreated or inadequately treated acute pyelonephritis or ascending urinary tract infection. More than rarely, it results from hematogenous spread from an extra-urinary source of infection (e.g., diverticulitis, pancreatitis). Patients may present with signs and symptoms of infection. Renal abscess tin can appear as a circuitous renal cyst with inhomogeneous areas of fluid attenuation/intensity and a thick and irregular wall that shows a little enhancement on excretory phase (Fig. 10). Because of the presence of viscous pus, the fluid component shows a characteristic stiff and heterogeneous improvidence restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging, which favors the diagnosis of renal abscess over that of RCC [47]. Renal parenchyma around the abscess can show low density/intensity on early on phases and delayed enhancement [48, 49]. Fat stranding is often constitute side by side to the renal abscess [50]. Gas tin be rarely nowadays inside the lesion and strongly suggests abscess formation. When imaging findings, clinical history and laboratory tests do not let a confident differentiation betwixt renal abscess and cystic RCC; biopsy/drainage should be performed to obtain the correct diagnosis.

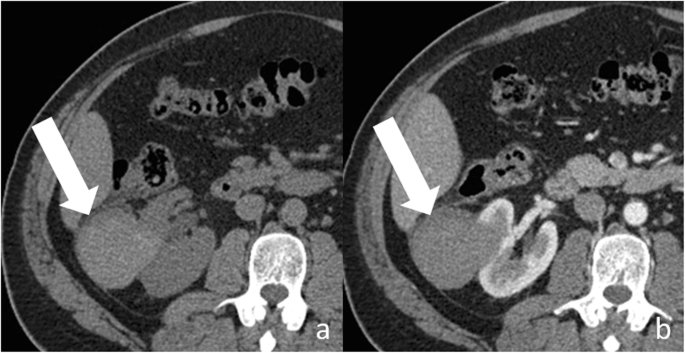

Renal abscess. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT shows a cystic lesion (pointer) with a peripheral, thick, enhancing, wall. b Axial dissimilarity-enhanced CT obtained 3 months after antibody therapy shows subtract in size of the lesion

Multifocal renal cysts

Multifocal cystic renal diseases comprise a heterogeneous spectrum of hereditary and nonhereditary diseases characterized by the presence of multiple simple kidney cysts [32]. Hereditary entities are due to mutations of genes involved in the germination and functioning of renal cilia, which event in epithelial proliferation and development of renal cysts [51]. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney affliction is the most common hereditary multifocal renal disease. Nonhereditary entities are due to obstructive, stromal-epithelial malinductive and neoplastic mechanisms [52]. Most common causes of nonhereditary multifocal cysts formation include lithium-induced nephrotoxicity, acquired cystic renal disease, and localized cystic renal disease. The location and advent of renal cysts, presence of interposed normal renal parenchyma, size of the kidneys, patient's age at presentation, and caste of renal function assist differentiate at imaging multifocal cystic renal diseases.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the virtually common hereditary renal disorder and occurs in approximately one of 500 alive births [51]. Mutations in one of the two genes encoding plasma membrane—spanning polycystin i and polycystin 2 (PKD1 and PKD2)—are responsible of the disease. It is characterized past progressive development and growth in size of uncomplicated renal cysts, leading to symmetric enlargement of the kidneys and chronic renal failure past late middle-historic period [52, 53] (Fig. 11). Cysts have variable dimension (from few millimeters to several centimeters) and are diffusely distributed through the kidneys. Cyst complications include hemorrhage, pyogenic infection, and, more rarely, rupture. The take a chance for RCC is non increased in comparison with the general population except in patients on dialysis [54]. The added take a chance of malignancy in dialysis patients is probably related to the effects of coexistent acquired cystic renal disease [54].

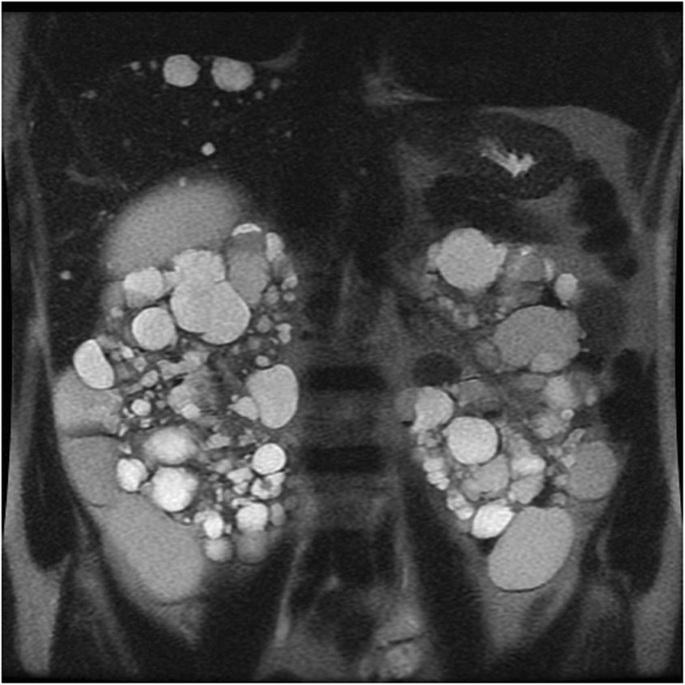

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Coronal T2-weighted image shows symmetric enlargement of the kidneys, which incorporate multiple cysts with variable size

Hepatic cysts are the well-nigh common extra-renal manifestations of ADPKD and show variable number, size, location, and distribution [51, 54]. Polycystic liver disease is uncommon and leads to hepatomegaly [51, 54]. More than rare hepatic complications include congenital hepatic fibrosis and segmental dilatation of biliary tract [54].

The other extra-renal manifestations of ADPKD include cysts in other organs such every bit pancreas and non-cystic abnormalities such as cardiac valvulopathies and intracranial aneurysms [51]. Imaging plays a crucial function in the identification of ADPKD in loftier-risk individuals (those with a positive family history). The diagnosis of ADPKD requires at least three renal cysts (unilateral or bilateral) in high-hazard patients 15–39 years of age, at least two cysts in each kidney in high-gamble patients 40–59 years of age, and several bilateral renal cysts in high-risk patients sixty years of age or older [55]. Since renal enlargement correlates with a decline of renal function, estimation of renal book can predict the hazard for renal failure [53].

Acquired cystic renal disease

Acquired cystic kidney disease (ACKD) is a event of sustained uremia in patient with end-phase renal disease [52]. The disease is found in 8–13% patients with end-stage renal affliction and in approximately 50% patients on dialysis. The disease is multifactorial. Information technology is the progressive destruction of renal operation nephrons with compensatory hypertrophy of remaining renal parenchyma, obstruction of renal tubules by interstitial fibrosis or oxalate crystals, and cyst formation [52]. Kidneys are atrophic and contain multiple cysts with variable size (from few millimeters to several centimeters) and imaging appearance (Fig. 12). Since renal cysts are extremely common in the developed population, the diagnosis of ACKD requires the presence of three or more than cysts in each kidney, in conjunction to end-stage renal illness, and no history of hereditable renal disease [56]. Cyst hemorrhage is a common complication and can cause hematuria, whereas cyst rupture, perinephric hematoma, and retroperitoneal hemorrhage are less frequent [52]. Development of RCC in the wall of the cyst is the most serious complication of ACKD, with a higher rate in comparison to the general population [55].

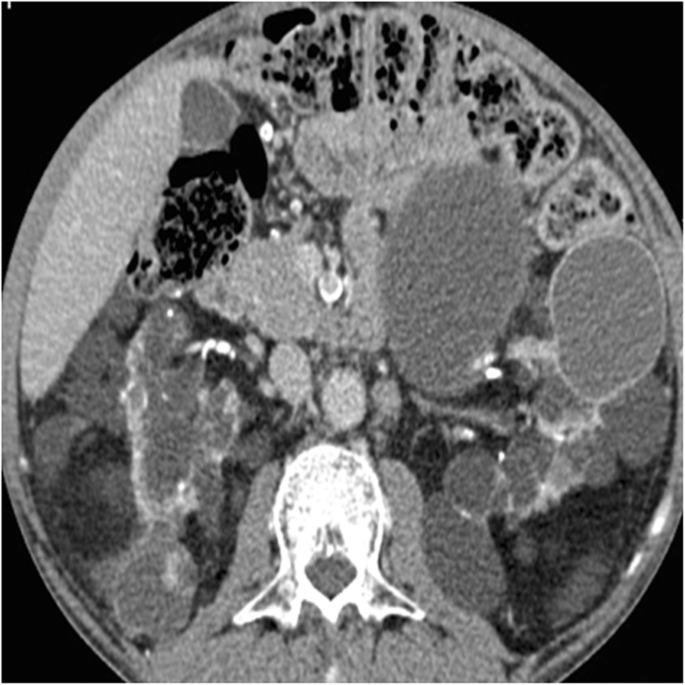

Acquired cystic renal illness. Centric contrast-enhanced CT epitome shows atrophic kidneys, which contain multiple cysts of variable size

The most common tumor blazon in patients with ACKD is acquired cystic disease (ACD)-associated RCC, followed past papillary and articulate cell blazon RCC [36]. ACD-associated RCC has unique morphologic features and is found exclusively in patients with cease-stage renal illness and ACKD [36].

Lithium-induced nephropathy

Long-term lithium therapy is a well-known cause of nephrotoxicity in the course of polyuria-polydipsia syndrome (diabetes insipidus) and chronic renal insufficiency [57]. Characteristic imaging findings include normal or slightly decreased size of kidneys with multiple, uniformly, and symmetrically distributed microcysts [58]. Microcysts measure ane–2 mm in diameter and are located in both cortex and medulla [58].

Localized cystic renal illness

Localized cystic renal disease is a rare, nonhereditary, form of cystic renal disease, which manifests as a conglomeration of multiple simple cysts of variable size [59] (Fig. 13). In contrast to ACKD and ADPKD, localized cystic renal affliction is typically unilateral and not progressive. The disease usually involves just a portion of the kidney with a polar predilection [59]. Entire renal involvement is rare [58]. The contralateral kidney is normal. The presence of interposed normal renal parenchyma and the absenteeism of a capsule assistance to differentiate localized cystic renal disease from cystic nephroma and multiloculated cystic RCC [58]. Cystic interest of other organs is typically absent [58].

Localized cystic renal disease. Axial dissimilarity-enhanced CT image shows a conglomeration of multiple elementary cysts of variable size (arrow) in the right kidney

Conclusions

Cystic renal lesions are commonly encountered on radiologic examinations. Complex and multifocal cystic renal lesions are often a diagnostic challenge, since they tin can correspond neoplastic and non-neoplastic weather. The Bosniak classification organisation is a well-established imaging method, which helps radiologists and surgeons in daily exercise in the differentiation of nonsurgical from surgical lesions. Radiologists should also recognize the imaging appearances of specific types of cystic lesions in order to improve characterize them.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ACKD:

-

Acquired cystic kidney disease

- ADPKD:

-

Autosomal ascendant polycystic kidney disease

- CEUS:

-

Contrast-enhanced United states

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MESTs:

-

Mixed epithelial and stromal tumors

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RCC:

-

Renal cell carcinoma

References

-

Hartman DS, Choyke PL, Hartman MS (2004) From the RSNA refresher courses: a practical approach to the cystic renal mass. Radiographics 24(Suppl 1):S101–S115 PMID: 15486234

-

Hélénon O, Crosnier A, Verkarre V, Merran S, Méjean A, Correas JM (2018) Simple and complex renal cysts in adults: classification system for renal cystic masses. Diagn Interv Imaging 99(four):189–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2017.10.005 PMID: 29482969

-

Park BK, Kim B, Kim SH, Ko K, Lee HM, Choi HY (2007) Assessment of cystic renal masses based on Bosniak classification: comparison of CT and contrast-enhanced Usa. Eur J Radiol 61(2):310–314 PMID: 17097844

-

Ascenti One thousand, Mazziotti S, Zimbaro G et al (2007) Complex cystic renal masses: label with contrast-enhanced US. Radiology 243(ane):158–165 PMID: 17392251

-

Corvino A, Catalano O, Corvino F, Sandomenico F, Petrillo A (2017) Diagnostic performance and confidence of dissimilarity-enhanced ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of cystic and cysticlike liver lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 209(iii):W119–W127. https://doi.org/x.2214/AJR.16.17062

-

Corvino A, Catalano O, Setola SV, Sandomenico F, Corvino F, Petrillo A (2015) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the characterization of circuitous cystic focal liver lesions. Ultrasound Med Biol 41(five):1301–1310. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.12.667

-

Corvino A, Sandomenico F, Setola SV, Corvino F, Tafuri D, Catalano O (2019) Morphological and dynamic evaluation of complex cystic focal liver lesions past dissimilarity-enhanced ultrasound: current state of the art. J Ultrasound 22(three):251–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-019-00385-2

-

Quaia E, Bertolotto Thou, Cioffi V et al (2008) Comparison of contrast-enhanced sonography with unenhanced sonography and contrast-enhanced CT in the diagnosis of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191(4):1239–1249. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.07.3546

-

Johnson PT, Horton KM, Fishman EK (2010) Optimizing detectability of renal pathology with MDCT: protocols, pearls, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194(iv):1001–1012. 20308503. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.09.3049

-

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2005) How I do it: evaluating renal masses. Radiology 236(2):441–450 PMID: 16040900

-

State of israel GM, Hindman N, Bosniak MA (2004) Evaluation of cystic renal masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification organisation. Radiology 231(2):365–371 PMID: 15128983

-

Terada N, Arai Y, Kinukawa N, Terai A (2008) The 10-year natural history of uncomplicated renal cysts. Urology 71(one):seven–eleven. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.urology.2007.07.075 PMID: 18242354

-

Carrim ZI, Murchison JT (2003) The prevalence of elementary renal and hepatic cysts detected by screw computed tomography. Clin Radiol 58(8):626–629 PMID: 12887956

-

Bosniak MA (1986) The electric current radiological arroyo to renal cysts. Radiology 158(1):i–10 PMID: 3510019

-

Bosniak MA (1997) The utilise of the Bosniak classification system for renal cysts and cystic tumors. J Urol 157(v):1852–1853 PMID: 9112545

-

Balci NC, Semelka RC, Patt RH et al (1999) Complex renal cysts: findings on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 172(6):1495–1500 PMID: 10350279

-

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2005) An update of the Bosniak renal cyst classification arrangement. Urology 66(3):484–488 PMID: 16140062

-

Benjaminov O, Atri M, O'Malley M, Lobo One thousand, Tomlinson G (2006) Enhancing component on CT to predict malignancy in cystic renal masses and interobserver understanding of different CT features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 186(3):665–672 PMID: 16498093

-

Galia M, Albano D, Bruno A et al (2017) Imaging features of solid renal masses. Br J Radiol xc(1077):20170077. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170077 PMID: 28590813

-

Mileto A, Allen BC, Pietryga JA et al (2017) Characterization of incidental renal mass with dual-energy CT: diagnostic accurateness of constructive atomic number maps for discriminating nonenhancing cysts from enhancing masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol 209(iv):W221–W230. https://doi.org/x.2214/AJR.16.17325 PMID: 28705069

-

Fananapazir Grand, Lamba R, Lewis B, Corwin MT, Naderi Southward, Troppmann C (2015) Utility of MRI in the characterization of indeterminate small renal lesions previously seen on screening CT scans of potential renal donor patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 205(ii):325–330. https://doi.org/ten.2214/AJR.14.13956 PMID: 26204282

-

State of israel GM, Bosniak MA (2003) Calcification in cystic renal masses: is it important in diagnosis? Radiology 226(i):47–52 PMID: 12511667

-

Baert L, Steg A (1977) Is the diverticulum of the distal and collecting tubules a preliminary phase of the unproblematic cyst in the adult? J Urol 118(5):707–710 PMID: 410950

-

Davarpanah AH, Spektor M, Mathur K, Israel GM (2016) Homogeneous T1 Hyperintense renal lesions with smooth borders: is contrast-enhanced MR imaging needed? Radiology 281(ane):326. https://doi.org/x.1148/radiol.2016164032 PMID:27643777

-

Silverman SG, Israel GM, Herts BR, Richie JP (2008) Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology 249(i):16–31. https://doi.org/x.1148/radiol.2491070783 PMID: 18796665

-

Bosniak MA (1993) Issues in the radiologic diagnosis of renal parenchymal tumors. Urol Clin North Am 20(two):217–230

-

Bosniak MA (1997) Diagnosis and direction of patients with complicated cystic lesions of the kidney. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169(3):819–821

-

Smith Advertisement, Remer EM, Cox KL et al (2012) Bosniak category IIF and III cystic renal lesions: outcomes and associations. Radiology 262(i):152–160. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11110888 PMID: 22106359

-

Hindman NM, Hecht EM, Bosniak MA (2014) Follow-up for Bosniak category 2F cystic renal lesions. Radiology 272(3):757–766. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14122908 PMID: 24766033

-

O'Malley RL, Godoy 1000, Hecht EM, Stifelman MD, Taneja SS (2009) Bosniak category IIF designation and surgery for complex renal cysts. J Urol. 182(iii):1091–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.046 PMID: 19616809

-

Bosniak MA (2012) The Bosniak renal cyst classification: 25 years later. Radiology 262(3):781–785. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11111595 PMID: 22357882

-

Wood CG tertiary, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB et al (2015) CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics 35(one):125–141. https://doi.org/ten.1148/rg.351130016 PMID: 25590393

-

Winters BR, Gore JL, Holt SK, Harper JD, Lin DW, Wright JL (2015) Cystic renal cell carcinoma carries an splendid prognosis regardless of tumor size. Urol Oncol 33(12):505.e9–505.13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.07.017 PMID: 26319351

-

Hartman DS, Davis CJ Jr, Johns T, Goldman SM (1986) Cystic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 28(2):145–153 PMID: 3739121

-

Moch H (2010) Cystic renal tumors: new entities and novel concepts. Adv Anat Pathol 17(3):209–214. https://doi.org/x.1097/PAP.0b013e3181d98c9d PMID:20418675

-

Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM (2016) The 2016 WHO Nomenclature of tumours of the urinary arrangement and male genital organs-role a: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol 70(1):93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.029 PMID: 26935559

-

Jhaveri Thousand, Gupta P, Elmi A et al (2013) Cystic renal cell carcinomas: practise they grow, metastasize, or recur? AJR Am J Roentgenol 201(2):W292–W296. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.12.9414 PMID: 23883243

-

Meilstrup JW, Mosher TJ, Dhadha RS, Hartman DS (1995) Other renal tumors. Semin Roentgenol 30:168–184

-

Bracken RB, Chica G, Johncon DE, Luna M (1979) Secondary renal neoplasms: an autopsy study. Southward Med J 72:806–807

-

Abrams H, Spira R, Goldstein Chiliad (1950) Metastases in carcinoma: analysis of 1000 autopsied cases. Cancer 3:74–85

-

Klinger ME (1951) Secondary tumors of the genitourinary tract. J Urol 65:144–153

-

Patel U, Ramachandran Due north, Halls J, Parthipun A, Slide C (2011) Synchronous renal masses in patients with a nonrenal malignancy: incidence of metastasis to the kidney versus primary renal neoplasia and differentiating features on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 197(iv):W680–W686. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.xi.6518 PMID: 21940540

-

Choyke PL, White EM, Zeman RK, Jaffe MH, Clark LR (1987) Renal metastases: clinicopathologic and radiologic correlation. Radiology 162(2):359–363 PMID: 3797648

-

Fan Thousand, Xie YU, Pei X et al (2015) Renal metastasis from cervical carcinoma presenting as a renal cyst: a instance report. Oncol Lett x(5):2761–2764

-

Moslemi MK (2010) Mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney or adult mesoblastic nephroma: an update. Urol J vii(3):141–147 PMID: 20845287

-

Lane BR, Campbell SC, Remer EM et al (2008) Adult cystic nephroma and mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney: clinical, radiographic, and pathologic characteristics. Urology 71:1142–1148

-

Goyal A, Sharma R, Bhalla As, Gamanagatti S, Seth A (2013) Improvidence-weighted MRI in inflammatory renal lesions: all that glitters is not RCC! Eur Radiol 23(1):272–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2577-0 PMID:22797980

-

Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Goldman SM (2000) Imaging in astute renal infection. BJU Int 86(Suppl ane):70–79 PMID: 10961277

-

Papanicolaou N, Pfister RC (1996) Astute renal infections. Radiol Clin North Am 34(v):965–995 PMID: 8784392

-

Katabathina VS, Kota G, Dasyam AK, Shanbhogue AK, Prasad SR (2010) Developed renal cystic affliction: a genetic, biological, and developmental primer. Radiographics 30(6):1509–1523. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.306105513 PMID: 21071372

-

Gabow PA (1993) Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 329(v):332–342 PMID: 8321262

-

Choyke PL (2000) Acquired cystic kidney illness. Eur Radiol 10(11):1716–1721 PMID: 11097395

-

Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB et al (2006) Book progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 354(20):2122–2130 PMID: 16707749

-

Chauveau D, Fakhouri F, Grünfeld JP (2000) Liver involvement in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: therapeutic dilemma. J Am Soc Nephrol. 11(9):1767–1775 Review. PubMed PMID: 10966503

-

Tickoo SK, de Peralta-Venturina MN, Harik LR et al (2006) Spectrum of epithelial neoplasms in end-phase renal disease: an experience from 66 tumor-bearing kidneys with emphasis on histologic patterns singled-out from those in desultory developed renal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol xxx(2):141–153 PMID: 16434887

-

Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A et al (2009) Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol twenty(i):205–212. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2008050507

-

Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, Valeri AM, Hines WH, D'Agati VD (2000) Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 11(8):1439–1448 PMID: 10906157

-

Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D et al (2003) Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiology 229(2):570–574 PMID: 14595154

-

Slywotzky CM, Bosniak MA (2001) Localized cystic affliction of the kidney. AJR Am J Roentgenol 176(4):843–849 PMID: 11264061

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted data

Publisher's Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and bespeak if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this commodity

Cite this article

Agnello, F., Albano, D., Micci, G. et al. CT and MR imaging of cystic renal lesions. Insights Imaging 11, five (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-019-0826-three

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s13244-019-0826-iii

Keywords

- Bosniak

- Cystic renal lesion

- Cystic renal jail cell carcinoma

- CT

- MR

Source: https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13244-019-0826-3

0 Response to "complex cyst on kidney has grown 5 mm i n 6:months what to do?"

Post a Comment